- Home

-

Qualifications

- Diploma in Nutrition and Health Coaching

- Womens Health and Wellness Coach Certification

- Certified Coaching Professional Program

- Diploma in Coaching for Lifestyle & Wellbeing Management

- Holistic Wellness Coaching Program

- The Ultimate Triple Qualification

- Health Coaching Electives

- Wellness Coaching for Professionals

- Coach Gap Training

- Professional Certificate in Meal and Menu Planning

- Accreditation, Registration & Insurance Options

- Degree & Diplomas

- Short Courses

- Testimonials

- Enrol

- FAQs

- About

- Contact

- Login

- Things We Do

Is a keto diet for everyone?Ketosis seems all the rage in dietary habits these days. But, is a keto diet for everyone? Is it safe? How hard is it to stick to? Is it another weight loss fad? Or is it using our ancestral origins to return to our predetermined ideal eating style? Let’s take a look at what a keto diet is, what happens when our body goes into ketosis, and what the benefits might be. First stop... What is the keto diet? You’ll see it as ‘keto diet’, ‘ketogenic diet’, ‘ketosis diet’ and so on, let’s save ourselves a few keystrokes and call it the KD. According to the Ketogenic Diet Plan Resources website, a ketogenic diet plan:

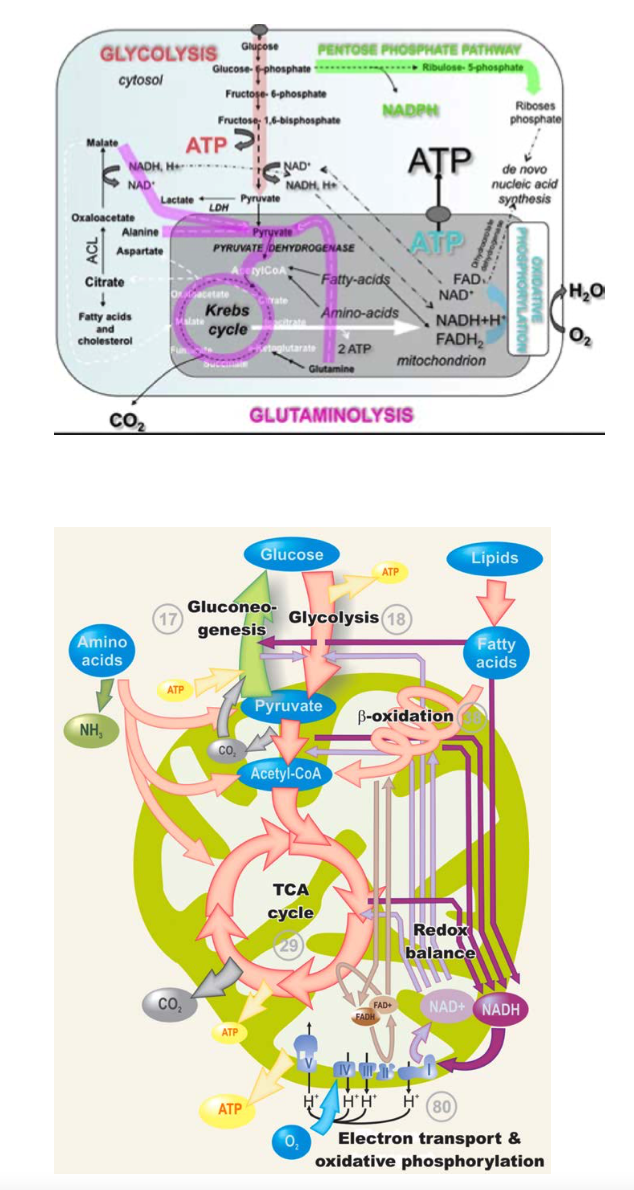

Sounds good, but what does ‘switching your primary cellular fuel source’ entail? Sounds a little tricky, in knowing a little about the finely tuned machine the human body is, the thought of switching anything seems like a big ask. We like to present a whole picture, that way you can make your own informed views, so yes, we’ll need to take a quick look at ‘ketosis’. Under normal conditions, our body happily chugs along on its diet of mainly carbs (about 60%) and then some protein and fat thrown in for good measure (so to speak). Carbs are integral in the generation of energy for activity and for basic human physiological processes. For example, the brain runs almost entirely on glucose which can easily pass the blood brain barrier (a barrier to prevent unwanted compounds entering the brain). Our eyes rely on glucose as do muscle cells and much more. But what happens when our supply of glucose runs short, we’ve depleted our stored glucose (glycogen in the muscle and liver), and the carbohydrate bank is all but spent? We’ve all heard of people stuck up on snow- covered peaks for days, months on end even. As the days pass and food supply dwindles the body has an amazing adaptation. Ketosis occurs when our primary fuel is running low and small amounts need to be conserved, our bodies take the bold move of switching to the use of protein, however in the process we produce bi-products that the body and particularly the brain don’t like a great deal... ketones. If you’ve ever fasted, or gone without food for a good period of a day you may have noticed a sweet smell on your breath, or someone might have noted this for you, likely you are in ketosis. Ketone bodies (ketones) move from our liver to other tissue, such as the brain to be used as fuel. In mobilising ketones the body can conserve any remaining glucose or glycogen. How did the keto diet come about?For many years we’ve obsessed with dietary fat as the root of our growing waste lines, only to find out that much of the rhetoric was based on assumption. We did an Animal House on fat, moving from ‘all fat bad’ to ‘saturated fat bad unsaturated fat good’, to more recently ‘some saturated fat bad, some saturated fat not bad and unsaturated fat good’. Confused? I’m not surprised. Remembering here at Well College a tend towards what we believe is the ultimate diet... the CSD. Excuse the digression... So, we ponder, if fat is not making us overweight, and if low-fat products created big bellys and even bigger manufacturing wallets then what is it... Sugar? It’s got to be sugar? Surely?! Couldn’t possibly be a variety of issues related to our 21st- century lifestyles... nooooo. So we shine the spotlight on sugar ‘you will tell us the truth sugar’! Yes, it’s true sugar can impact on body fat, excess sugar while not being converted to fat (yes, sugar does not turn to fat, the process of de novo lipogensis, making of fat from a non-fat compound (sugar), occurs in such small amounts in the human body that it doesn't have a significant impact on body fat. Look it up, or take our short course on this if you want to get to grips with this, some of you may be shaking your heads, but it’s one of the great myths in nutrition. The role that carbs have in body fat is linked to insulin. When we eat carbs, our body produces insulin to help our cells open up and allow the glucose from the blood to enter the cells to be used as fuel. Any carbs we don't burn up or use in some way we excrete through the urine and balance is maintained. Remember, the body is all about balance. Hmmm, funny that, balance is exactly what we push! Anyway, insulin is often referred to as our ‘fat hormone’, that is when it’s present our bodies store more available fat and retain the fat that is stored, a net gain in other words. It’s true that as long as you have a constant supply of carbs your body is likely to use this first. Carbs are easy to digest, require little transformation to be used as a fuel and move about the body quite easily under normal circumstances. In theory this means that if you have enjoyed many years of a diet with lots of dietary fat that has not been required for energy (in other words there has been no deficit of carbs to enlist stored fuels like fat) then the fat piggy bank continues to grow under this condition. Your banking is made up of dietary fat and the storage of these is enhanced under insulin release in order to metabolise carbs. Let's check out the process of ketosisAfter a prolonged absence of fuel (glucose), which naturally means we’ve less circulating insulin, the body moves to conserve what glucose remains, and instead turns to fat as a form of fuel. A few of you may be clapping your hands at the thought of this, but hold your horses, there’s more to it than that... groans... of course. We now have the situation that glucose is so low that it isn’t able to drive normal fat use/oxidation (for our techy folk, this is a result of the lack of oxaloacetate which is required for energy production in the Krebs cycle), or fuel the central nervous system (specifically the brain). After a few hours in this state the body needs to find an alternative source of fuel, yep and here’s where it switches to using fat. That is the short story... In the process of producing energy our cells make a substance called acetoacetate from another energy-related compound called acetoacetyle CoA (or acetyle coenzyme A or just CoA). Under normal conditions compounds such as acetoacetic acid are limited, they are easily metabolised by the body tissue. However, when there is a short supply of glucose the body in attempts to boost energy supply makes too much CoA, and the result is a higher rate of production of compounds called ketone bodies (KB). As glucose continues to be in short supply KBs can build up in the body, in extreme cases KBs build-up in the blood (ketonemia) and in the urine (ketonuria) as the body attempts to find balance. You know that sweet-smelling breath someone gets when they’ve been fasting? This is one of the signs of ketosis, it’s actually acetone which is a bi-product of KB’s. How do ketone bodies improve energy supply?Ketone bodies (ketones), which are produced in the liver mitochondria cells (this process is called ketogenesis), are said to be glucose-energy sparing and prevents breakdown of proteins, they include substances called acetoacetate (acetoacetic acid), which is quickly converted to acetone), beta-hydroxybutyric acid (βOHB, the main KB used by the body, remember this one we’ll be talking a lot more about it soon) and acetone (yes the one in the same as nail polish remover, acetone is the main ingredient). Oh, and it’s worth noting that insulin inhibits ketogenesis. Traditionally nutritionists were taught ketosis was always a bad thing, lets draw a distinction here. Typically, when we talk about ketosis we are talking about it in reference to a pathophysiological condition, diabetes. KBs in our blood on any normal day are at a much lower level than glucose, around 0.3 millimoles per litre (mmol/l) of blood. It’s not until they reach a concentration of 4 mmol/l (the same level as glucose) that they’ll be used to produce fuel by the cells of body, including the brain but not the liver. It’s thought that the upper level of KBs recommended in a ketogenic diet is 8 mmol/l (Paoli, 2014), beyond this, things tend to become less than desirable. If you glance at Table XX below you can see that at the extreme end ketoacidosis occurs, the blood pH is not sustainable and loss of consciousness and death can occur, we’ve all seen this in movies where a Type 1 diabetic (who can’t make insulin) goes into a diabetic coma after not having their insulin injection. The ketosis that I’m referring to in this blog is nothing to do with this, it is about inducing a mild state of ketosis in order to alter fuel selection in the body. Take a quick squiz at Table 1, you can see how a diabetic ketoacidosis differs markedly from a ketogenic diet state, it’s a significant difference in glucose and of course notably insulin is zero, KBs are 25 or more per mmol/l and the pH is below ideal. Table 1 Blood levels during a normal diet, ketogenic diet and diabetic diabetic ketoacidosis

Source: Paoli, 2013 Ketone bodies as energyWe’ve looked at CoA and how it’s a compound used to create energy. KBs are pretty efficient at creating energy. Remember βOHB? Good, βOHB produces two molecules of acetyl CoA (energy which then enters the Krebs cycle to really get busy making fuel called ATP). It was of interest to me to learn that KBs produce more energy than glucose as the process of ketosis leads to more ATP. And, if this weren’t enough glucose in the blood appears to be maintained at reasonable levels during ketosis. Seems our bodies are able to make enough glucose from using glucogenic amino acids and the glycerol from the breakdown of triglycerides. In fact, it seems that up to 60% of our glucose can be formed from glycogenic amino acids and glycerol during ketosis. While it sounds a little challenging to find the right ‘level’, ketosis isn’t as scary as many might expect it was going to be. Table 2 Glucogenic and Ketogenic Amino Acids

Here’s another interesting tid bit that might be new to many; our little ones produce and use KBs more readily and easily than we adults, and the elderly also appear to use KBs reasonably well too. In researching the keto diets you will see discussion around the evolutionary aspect, that we have ancestrally used ketones as fuel, certainly this is born out when looking at bacterial synthesis of KBs (Newman and Verdin, 2014). What does a ketogenic diet look like?Tracking down the actual ketosis diet is a tricky task, there are a lot of views on how many carbs you should eat and of what type, how much fat, how much protein, what foods are in, what are out. Clearly, there are a few takes on a working keto diet, but at the end of the day they are aiming for the same figures. When you are talking about levels of something in the bloody you are sitting firmly in a clinical realm. In trying to emulate by rough estimate a clinical situation the many individual factors will yield enormous vulnerability and variation. Here’s a bit of a rough guide though: Keto diets:

Some refer to ratios of the macronutrients, for example, 4:1 (fat to carbs), or 3:1 and so on. 20-50g of carbohydrates a day is not a great day, consider that 100g of soba noodles is 79g of carbs, 100g of dried dates has 67g of carbs, protein powder (30%) per 100g has 65g of carbs, 100g of salted corn chips gives you 58g of carbs, an apple has about 20g and a slice of bread 15g... you get the picture. On a keto diet, you are encouraged to eat:

You may be baulking at the restrictive nature of the diet and how restriction in terms of the psychology of eating and nutrient diversity isn’t generally ideal, certainly it challenges our college’s stance of a non-diet approach to eating. Aside from the challenge of the restrictions, some report feeling heady and struggling to focus as the brain adjusts to a different fuel source so this can compound the challenge of the change. Other changes that might influence progress include feeling sluggish, nausea, bad breath, constipation and altered sleep patterns. Source: http://www.wormbook.org/chapters/www_intermetaboli sm/intermetabfig1.jpg What does the science say so far?We started out looking generally at keto diet research and was overwhelmed with the amount of studies across many areas, longevity, weight loss, diabetes, blood lipids, appetite control, satiety, epilepsy, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and more, keeping in mind many of the studies are animal studies. The list of benefits includes a decline in type two diabetes, reversing kidney damage as well as diabetic nerve damage, improved blood lipid profiles and cardiovascular outcomes. There are increasing studies, at this stage mostly in animals, suggesting that a KD may potentiate some chemotherapies, and reduce growth of some tumors, for example, glioma. One of the challenges in cancer therapies is to cut off the supply of energy to the cancer cells (they use glucose), it seems that a keto diet create a metabolic change in energy production which affects the energy source for tumor cells and inhibits their growth, tumor cells aren’t able to metabolise ketones for energy, thereby improving survival rates (Woolf and Scheck, 2015). It appears that it’s this altered fuel production that is the key to many of the potentially beneficial outcomes. Some have gone as far to suggest that KBs are “superfuels” ad that even beyond this seemingly impressive fuel option KBs, well specifically β- hydroxybutyrate, also appear to act as signals involved in the inhibition of compounds involved in disease processes at a gene transcription level (Newman and Verdin, 2014), enter epigenetics! Again, if you’re totally into the techy side of things, KBs appear to influence at least two cell receptors, and inhibit a class of compounds (HDACs) that interfere with gene expression, when allowed to party HDACs appear to be involved in cancer. Are there downsides?Ketogenic diets aren’t necessarily right for everyone, and some underlying health challenges might not make this a suitable diet for some. Of course the dieting pattern this can put people into and resulting body dysmorphia and other outcomes may be an issue for some and as we know yo-yo diets can lead to overall weight gain over the long term and negative health outcomes. There was some debate over discrepancies in findings of weight gain and weight loss. It appears that the composition of the macronutrients in the ketogenic diet may be at play here, specifically the percentage of protein (Newman and Verdin, 2014). In lowering both carbs and protein (in some ketogenic diets as low as 5%) this puts total fat intake at a whopping figure. Keeping in mind a high-fat diet alone does not seem to exhibit the same benefits as a high fat keto diet (Newman and Verdin, 2014), and high protein diets may reduce lifespan (from destruction of our telomeres on the end of our genes causing them to unravel a little like an old shoelace does, there is a fine balance to achieve. There was some discussion of increased oxidative stress, but it’s either too early or just not there. Making sense of itThe question it seems is what level of ketosis is ideal to suppress eating, lose weight and yet be achieving a varied diet? Many of us have a friend who is on a self-imposed low carb diet. For example, he or she may happily admit to eating two eggs and bacon for brekky each day, and a chop for dinner. Yes, missing many foods, watery fresh tastes of fruit, although he does have some fruit. They might admit it's a low carb diet, not a no-carb diet, but rarely eat vegetables or grains. Many of us will want to encourage they to eat more variety, more colour, more produce, more fibre. We might worry about their vitamin C, about their antioxidant compounds, and so on. But, they are looking great and report feeling great, perhaps saying they haven’t felt this good in years, their blood cholesterol may be fine, and they feel well. Additionally, there are concerns around the environment, plants are widely believed to be more sustainable than animals, and for some the ethical concerns are there too. One of the things we say here at Well College is that most diets (and as you know we are not pro-dieting) offer some benefit, whether it’s by virtue of cutting out the crap or just trying new foods, and if you are interested in understanding a diet a great way there are two great strategies to forming an informed view. Try it first Read widely and be objective Well College is not funded by any organisations, this article is written from an objective educative viewpoint. Seek medical advice if you’re not feeling tip top. References Azar, Sami T., Hanadi M. Beydoun, and Marwa R. Albadri. "Benefits of Ketogenic Diet For Management of Type Two Diabetes: A Review." Journal of Obesity & Eating Disorders (2016). Dragieva, Pamela, et al. "Does a Ketogenic Diet Influence Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease?." Scripta Scientifica Vox Studentium 1.1 (2017). Beckett, Tina L., et al. "A ketogenic diet improves motor performance but does not affect β-amyloid levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer's Disease." Brain research 1505 (2013): 61-67. Benard et al., 2010. Multi-site control and regulation of mitchonrial energy production. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, vol 1797, Issue 6-7, 2010. Gibson, Alice A., et al. "Do ketogenic diets really suppress appetite? A systematic review and meta-analysis." Obesity reviews 16.1 (2015): 64-76. Manninen AH. Metabolic Effects of the Very-Low-Carbohydrate Diets: Misunderstood “Villains” of Human Metabolism. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2004;1(2):7-11. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-1-2-7. Newman, John C., and Eric Verdin. "Ketone bodies as signaling metabolites." Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 25.1 (2014): 42-52. Paoli A (2014) Ketogenic diet for obesity: friend or foe? Int J Environ Res Public Health 11: 2092-2107. Paoli et al. Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2013) 67, 789–796; doi:10.1038/ejcn.2013.116; published online 26 June 2013 AuthorWell College Global. 2019-2020. Extract from the Certificate of Human Nutrition.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsBev Whyfon; Bev's Healthy Food Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

CONNECT WITH US

|

- Home

-

Qualifications

- Diploma in Nutrition and Health Coaching

- Womens Health and Wellness Coach Certification

- Certified Coaching Professional Program

- Diploma in Coaching for Lifestyle & Wellbeing Management

- Holistic Wellness Coaching Program

- The Ultimate Triple Qualification

- Health Coaching Electives

- Wellness Coaching for Professionals

- Coach Gap Training

- Professional Certificate in Meal and Menu Planning

- Accreditation, Registration & Insurance Options

- Degree & Diplomas

- Short Courses

- Testimonials

- Enrol

- FAQs

- About

- Contact

- Login

- Things We Do

RSS Feed

RSS Feed